MOZART, THE FREE MASONS AND A MYSTERIOUS DEATH

As death, when we come to consider it closely, is the true goal of our existence, I have formed during the last few years such close relationships with this best and truest friends of mankind that death’s image is not only no longer terrifying to me, but is indeed very soothing and consoling. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Mozart wrote his first masonic work at age 16 (1772) when he was commissioned to write music for the Bavarian lodge “Zur Behutsamkeit” (translated: with Restraint). Twelve years later, at age 28, just three years after moving to Vienna, Mozart became one of 32 members of the Vienna mason lodge, “Zur Wohltätigkeit” (translated: Charity) on December 14, 1784. His rise amongst his fellow lodge brothers was swift. Within three weeks, on January 7, 1785, he ascended to the position of “journeyman” and in less than a month after that, on February 1, 1785, became a “master.” Lodges were composed of varying members of society and “Zur Wohltätigkeit” was a bourgeoisie lodge, consisting of middle class intellectuals and quite a few Illuminati.

A bit over two months after Mozart became a master in his lodge, his father, Leopold, also joined “Zur Wohltätigkeit.” But not even the connections that he no doubt secured through life as free mason, were enough to help accelerate Mozart’s income to keep pace with his increasing I-O-Us. By the summer of 1788 things came to a head when Mozart began appealing to his masonic brother Michael Puchberg, for loans. A letter in June 1788 from Mozart to Puchberg begins: “Dear Brother! Your true friendship and brotherly love embolden me to ask an enormous favor of you…” His letters begging for money continued on into 1791, the year when Mozart composed his final great work —the Magic Flute with references to many of the free mason symbols, rituals, themes and beliefs (more in next post: Mozart, the Free Masons and the Magic Flute).

“The music is not in the notes, but in the silence between.”

Around the same time, a mysterious stranger showed up on his doorstep as a messenger of a man who did not wish to be known but wanted to commission Mozart to write a Requiem for a person “who is and forever would be very dear to him.” The stranger paid cash and Mozart was in no position to turn it down. The composer had a law suit pending against him and his family for money he owed to Prince Lichnowsky — the equivalent of what today would amount to over 50,000 USD. In the end, however, the assignment plagued him and Mozart became obsessed with the idea that he was writing the Requiem for himself. Convinced that he had been poisoned with acqua toffana (an Italian-made arsenic that young wives liked to use to hasten their widowhood), Mozart told his wife, Constanze, that he feared he must die.

Just a a bit over a month after the premiere of The Magic Flute, in November 1791 Mozart became bedridden for 15 days. Family members reported that at first his hands and feet swelled, and then he was almost completely unable to move. This was followed by vomiting.

Mozart died on December 5, 1791. He was 35 years old.

On the day of his death he asked for the score to be brought to his bedside. ‘Did I not say before, that I was writing this Requiem for myself?’ After saying this, he looked yet again with tears in his eyes through the whole work. – Biographer Niemetschek

After Mozart’s death, the stranger came once again to fetch the unfinished Requiem. The mystery was apparently solved — the Requiem had been commissioned by a count for his dying wife. He had commissioned several works of music and had intended to publish them in his own name.

Nevertheless, many have theorized about the causes of the sudden death and poisoned-like appearance of the body of the seemingly healthy Mozart – amongst them Russian writer, Alexander Pushkin, in one of his short plays known as The Little Tragedies and written in 1830 and entitled Mozart and Salieri. Did fellow composer, Antonio Salieri, murder Mozart? The two seemed to get along so well. In fact, in October 1791, not even two months before he died, Mozart had even taken along Salieri and his mistress in his carriage to a performance of The Magic Flute, where they sat with Mozart in his box.

Conspiracy theories of Mozart’s death abound, including one that blames the free masons for killing Mozart for revealing free mason secrets in The Magic Flute.

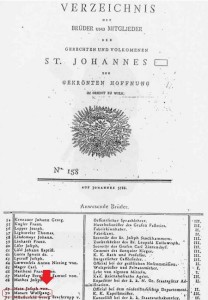

Yet if Orations are any indication, Mozart’s Masonic brothers, did indeed seem sorry to see him go. The following text stems from the Circular Letter of the Lodge “zur Neugekrönten Hoffnung” (translated: Newly Crowned Hope) on Mozart’s Death, Read upon the Admission of a Master to the Venerable St. John.

The Great Architect of the Universe was obliged to wrest one of most beloved, most deserving members from our fraternal chain. Who did not know him?— who did not cherish him?— who did not love him?— our worthy brother Mozart – It was only a few weeks ago that he stood here amongst us, that he glorified the consecration of our Masonic Temple with enchanted tones. – Vienna, April 1792

Mozart’s funeral service was held in Vienna’s grand St. Stephan’s Cathedral. He was buried, as was customary at the time for folks who were not upper class or nobility, in a mass grave in Vienna’s St. Marx cemetery.

Read more about the poison theory and Mozart’s death: http://www.sierranevada.edu/snow/WhatKilledMozart.htm

Want to read more about Mozart and the Free Masons? Check on this book: Angermüller, Rudolph. Mozart’s Masonic Music. Vienna: Mozarthaus, 2015. Print.

In Vienna? Pay a visit to the Mozarthaus Vienna which currently has an exhibit about Mozart, the free masons and the Magic Flute. From the room believed to have been his billiard room, Mozart would have been gazed into the cobble-stoned lane of the Blutgasse (Blood Lane), which is also tied to the tales of the free masons and Knights of Templar.